Sampling Identity: The Work of Carla Gannis

Identity is the cornerstone of our being and the means by which we impose some small degree of order upon the world, which is always in a state of growth and flux. What we may or may not comprehend is that identity itself is likewise in flux, and though we may often hold to the belief that it represents a fixed quantity, we are hard-pressed to decide which elements define our individual ideas of our selves. In history, when mankind has been in a state of doubt, it has searched for symbols to represent the qualities it most admires or despises. Those first took the form of mythology, then later of religious devotion, and much later—and in some ways finally—the precepts of science. The journey through belief is itself a journey to self-knowledge, and it is through art that man has often found himself seated before not only a fount of valuable learning, but also before a mystery whose purpose has yet to be told.

Individual artists throughout history have created oeuvres that present pictorial views of reality which impress upon the viewer a regard for beauty and order, for depravity and chaos, and for the mystery and opacity of abstraction. A common thread between each of these aesthetic agendas has been that the works reveal a degree of symbolism that relates directly to our manner of approach, and not to the overt subject matter on view. We must be able to take from the work of various artists what is given, in the combinations of complex and hybrid meaning that are intended. Symbolism works best when it is connected to a depiction of reality that is loaded with varied degrees of context yet allows us to detach ourselves and consider a work’s themes without any expectation that it will fall in line, aesthetically or morally, with the mundane aspects of our daily lives. What art reveals is the connection between conscious and unconscious recognition, whether that relates to fantasy versus reality or to accepted versus taboo ideas and beliefs.

Carla Gannis utilizes the appearance of reality to create a context of transparent pastiche which ironically juxtaposes received knowledge with aesthetic phenomenon. Her characters are sampled from various cultural contexts, including her own life, art history, mythology, and the mainstream media; yet a working knowledge of the inner recesses and psyche of the artist's life may be necessary in order to gainsay the character of each image. Whether through individual choice or the agency of unseen forces, every character expresses a loaded and subjective vulnerability, either by appearance or mood, or by a transformation depicted in the physical situation. Likewise, the situations themselves, as paired with the actions of her characters, are made to represent a perverted perspective of the logic behind narrative and causality. This is achieved by her use of the "sample," a technique that is relatively new in cultural terms, though it is similar in effect to gene-splicing, when scientists combine, for example, the genes of different flowers to experiment with the physical consequences of crossbreeding. As a cultural process, sampling became popular in the early 1980s with rap music, in which musicians would take a passage of music from another artist's recordings and layer their own tunes or words over it. This began to occur in other musical forms over time. The synth-pop band Depeche Mode became especially well known for its practice of sampling such disparate sounds as spinning helicopter blades, shattering glass, or skidding car brakes, and adding them to a rhythmic or syncopated beat to form the backbone for their songs. In the age of digital culture, sampling has become a very accessible practice that allows artists to combine images from various origins and seamlessly meld them into an overt new reality.

Such is the case in Gannis's "Travelogue Series". The concept of narrative is a strong element in these works. Each of the images tells a story, and though very little is provided for the viewer to draw a conclusion, it is clear that there is more going on than what is depicted. The narrative that Gannis wants to show us is essentially a psychological one, in which factual details are not as important as emotional ones. Each story has to do with a strong psychic impression that she has held at one time or another. The degree of portent they hold and the manner of symbolism used to express that portent are the more telling qualities of her intention than anything more formal and explicit could suggest. For every period of emotional education in our lives there have been 'psychic turns,' moments of instantaneous clarity that have allowed us insight into the depth of our inner growth. Through these moments we are able to classify the movement from one state of being to another. From the inherent narrative quality of Gannis's imagery it can readily be surmised that she wishes to express the complexity of her issues in transit.

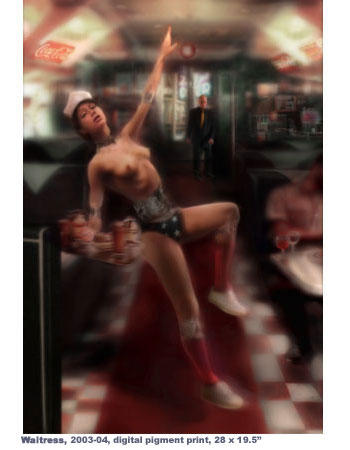

Because the sense of reality Gannis seeks to impart is necessarily complex, it obligates the viewer, when looking for meaning to take on the whole image, replete with all of its visual and contextual associations. We must start with the myths that are built into them, and work back toward a description of the commonplace. In WAITRESS, for instance, we have a figure that is clearly a woman, but the kind of woman we see depends upon the order in which we accept the various symbolic aspects of her appearance and the dramatic situation she inhabits. Her assigned role is given her by the work's title, but she is plainly more than that. She wears the costume of a comic-book super hero, her body naked from the waist up. In the area that would comprise her stomach and her womb, there is only a spine, with her stomach and womb neatly excised from the ideal representation of female form that she otherwise fulfills. The setting is a traditional diner with leather booths, a long red carpet down the middle, and red-and-white "Coca-Cola" signs overhead. The situation in which the waitress is posed provides another puzzling context. She is paused in midair, as if she were about to leap into action. It is clear that WAITRESS presents us with a complex symbol simultaneously representing different models of female identity. The character is swathed in identities that together show us how narrative can be created from the depiction of an emotional state, and conversely, how an emotional state can be projected upon the viewer which generates an empathic reaction that is both symbolic and personal. The character in this scene is clearly a symbol of strength, one that exists to heighten our regard for pedestrian reality, and yet she is no mean caricature, governed equally by idiosyncrasy as by heroism. She does not need to be involved in some cosmic clash or daring rescue to possess the rank we give her; her position as a mere wage slave presses this upon us. Her further state, in which she is deprived of the attributes that biologically define her and make her human, such as the need for sustenance and procreation. Gannis sets the stage for our reactions just as she manipulates the view. She wants us to understand that truth is not a one-sided coin, and that just as all persons can be symbols, such symbols can mean, and achieve, as much as individuals do in their private lives.

In LAST DAYS IN MEXICO we are presented with the scene of a crime in which there are three players, the villain, his victim, and a mysterious witness. The crime is a murder. A man in a dapper suit stands above a prone Pan-like figure with the furry body and cloven hoofs of a goat and the face of a woman. The setting is a large warehouse with one bright light high above on the ceiling, and the otherwise drab appearance of dirty white and industrial green paint. The Pan figure is joined in his fate by a naked woman with two moaning heads and wings that resemble those of a demonic butterfly. She is Hecate, queen of the underworld, a spirit who is present in the endgame of the hunt, and who presides over every event deemed a moral crossroads in life. She is a pagan figure, just as is Pan, and though he is a symbol of the decadence of late Greek society, she is a primordial figure who was once the Empress of Hell, predating even Hades himself. Her presence lends a sense of pathos to the death of Pan, and a vulnerability to the one human pawn here, who though he has been the harbinger of a certain decree of fate, is at this moment considering the efficacy of his role, lost in his houghts, thinking of the future.

A third and final example is THE BLUE CAR, another image that depicts a figure in the garb of a comic-book superhero, this one suggesting Superman, though in this case the character does not resemble our memory of him in the least. Our hero here is a small figure, curled into a fetal position as if sleeping, hanging upside down like a bat, with his cape wafting down to just above the surface of the earth. There is a lone witness to this event—a blue car that passes him in the middle distance—which makes us wonder about the identity of his spectators and of their intentions while he is both literally and figuratively 'wrapped up in himself.' We are made to feel a paternal or proprietary empathy for the sleeping hero, and a sense of dread for any unknown entity, even one provided by as innocuous a source as a simple automobile.

As Francis Bacon said, "knowledge is power." Yet knowledge comes to us from various sources, and identity is the sieve through which such gleanings are processed. If we can say, this is who I am, then we are inviting chaos and mystery into our lives. Yet the progress of history has shown us that there are many directions from which knowledge can be approached. There is the scientific method, which is primarily deductive, and which looks at physical details and makes assumptions that usually fall in line with preconceived notions. Alternately, there is the symbolic method, found in Gannis’s images, in which a vast and unforeseen psychic province is tapped through the use of complex narratives that introduce us to characters who are as opaque as their symbols. The narrative and the symbolic intersect in these images, obscuring any one path to understanding, and moreover, subverting the misconception that there can be only one story in each image. As a means of emotional education, they are thrilling and mysterious models for the shape of our common unconscious, and the transitional quality they impart proves a doubly rich context for the evolution of aesthetic perception.

Catalogue essay accompanying the exhibition "Carla Gannis: Travelogue" at Pablo's Birthday, 84 Franklin Street, New York, November 11 to December 7, 2004

8/27/05

Comments